I like to say that I was “raised by the village” throughout my childhood in Compton. Growing up in South Los Angeles — an economically challenged, heavily Black and Latinx area — often meant being raised not just by your parents, but by aunts, uncles, grandparents and other family members. For me, someone with four generations of relatives buried at Lincoln Memorial Park Cemetery in nearby Carson, it was no different. Life in Compton was a full-blown, multi-generational family affair.

Being part of the proverbial village also meant I had a unique lens into the community’s everyday struggle to survive, a struggle exacerbated at the time by the 1980s crack epidemic. I watched everyone from teenagers and young adults to the middle-aged and elderly fight from moment to moment to pay the rent, keep food on the table and push for a better life — or simply stay alive.

Even amidst the violence and turmoil of South L.A. life, we as a community looked out for each other. You weren’t left “floating in the wind,” but given real help. That altruistic attitude of always lending a hand has been close to my heart ever since.

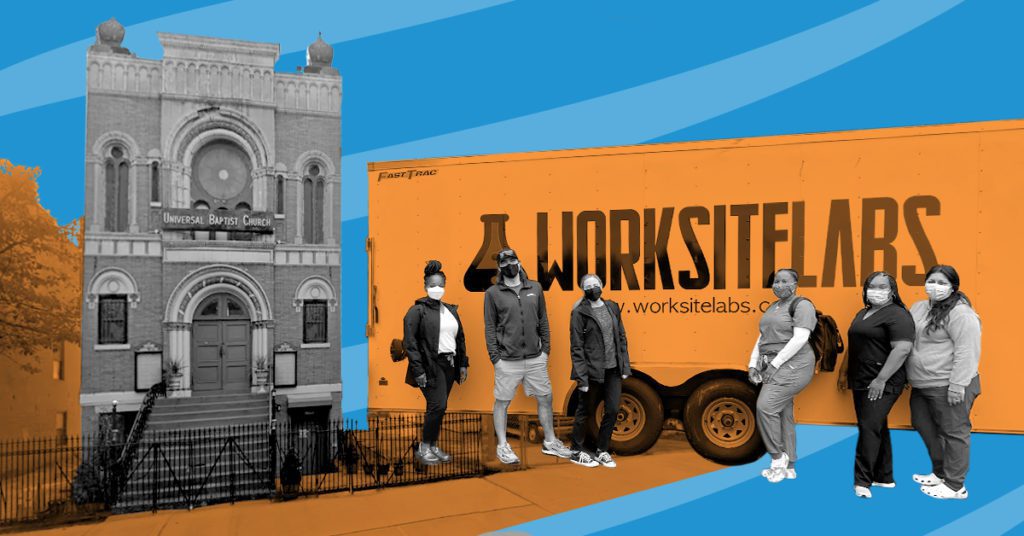

That’s why Worksite Labs has assembled new testing and vaccination sites in South L.A. and the Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood of Brooklyn, New York: To provide aid where it is most sorely needed, yet often sparingly granted.

The community need

Minority populations in the United States have long had a shaky relationship with public health, a reality COVID-19 continues to highlight.

The Center For Disease and Control and Prevention puts it best by calling race and ethnicity “risk markers” for other health-affecting conditions, such as socioeconomic status and healthcare access. As such, African Americans and Latinx individuals are roughly three times as likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 and twice as likely to die from it. While those numbers are frightening on their own, further troubling is that higher hospitalization and death rates for those groups have held largely steady for more than a year.

This is far from the first hint as to why minority residents are skeptical of public healthcare. After all, our nation allowed the Tuskegee Study to continue for 40 years. So it didn’t come as a surprise when Black and Latinx Americans initially were hesitant to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.

That skepticism seems to have waned in recent months, as 75% of Black Americans and 69% of Latinx recently said they’ve been vaccinated or plan to be, compared to 73% of white Americans. But if people of color are warming up to the idea of inoculation, why do Black and Latinx Americans remain the least-vaccinated ethnic groups?

Low accessibility must be part of that explanation. Minority residents of lower socioeconomic status tend to have trouble finding transportation, childcare or time off to receive the vaccine or can’t find a provider who speaks their own language.

Connections — and trust — are everything

To address the issues of access and trust in the Black and Latinx communities of South L.A. and Bed-Stuy — two of our country’s densest urban neighborhoods — the most valuable point of contact was obvious: the church.

Let’s go back to my upbringing for a minute. If you lived in Compton and were raised by a collection of relatives, odds are the older adults took you to Sunday service. Maybe you visited one church with one grandmother and a different church with the other. Maybe you didn’t find yourself sitting in a pew every Sunday, but I’ll bet church took some of your time if you had a childhood like mine.

For my family and many others, the Black church is synonymous with family. If you know somebody in the African American community, you’ll likely have instant access to their pastor or deacon. I can call any Black friend in this country, and, next thing I know, I’m in contact with their church leader.

That’s exactly how I got in touch with Reverend Dr. James R. Green Jr. of Universal Baptist Church in Bed-Stuy. While visiting to set up the Worksite Labs site at JFK Airport, I contacted my friend Mike Keller, who runs one of the state’s largest Black-owned construction companies, to help with a real estate matter. When he learned of our work to battle COVID-19, he immediately brought up his pastor and his church.

One thing led to another, and I was on the phone with Dr. Green, who describes UBC as a “community-minded church.” In his words, “We are always trying to do whatever we can do to enhance the lives of not just our membership, but the community at large. There are still a lot of people who have not yet been tested and have not been vaccinated. We thought it would be a good idea for us to show some assistance.”

As it turned out, UBC had an empty, paved plot of land next to its building that was going to go unused for a while — the perfect opportunity for a COVID testing and vaccination site. And that was that.

The formation of the South L.A. site was equally serendipitous, where I heard from a gentleman I grew up who is still close with my mom. He’s now a deacon at Peace Chapel Church, feeding the community, conducting work-life training workshops, hosting job fairs and finding other ways to help his neighbors as their outreach has grown fourfold in just five years. Since the early days of the pandemic, Rider Paysinger and Pastor DeAntwan Fitts have been working to supply residents with masks, hand sanitizers and 500 boxes of fresh fruits and vegetables every Friday for a year.

Rider knew I was in healthcare and asked whether I knew anything about vaccinations and community health during the pandemic, as they look for community partners who can deliver resources. Evidently, I knew a thing or two. As he put it, their church – which lost a key leader to COVID – is “doing what makes our hearts beat.” Fitts says their mission with Worksite Labs is to provide access and information to those in their communities to make their own choices.

As I said earlier, those in these communities of color look out for each other. In many parts of the country, the church plays a major role in fostering that sense of goodwill and trust. Serving our friends in the church helped Worksite Labs earn people’s confidence, assuring people that they are receiving quality, dependable care.

How we’re helping

Our Brooklyn and South L.A. sites, to open this summer, will differ considerably from our other COVID-19 testing locations. We will augment testing with providing doses of vaccine. But the biggest infrastructure change is the people.

Our bilingual team will provide community members with care they can understand. Our staffers practice faith community nursing led by our Chief Clinical Officer, Dr. Lindsay Williams, where they administer clinical services and counseling to those who might want additional education on testing and vaccines. In other words, they have the skillsets to meet people where they are. Dedicated full-time staff will also operate our signature shipping containers-turned-COVID- testing labs, which will be parked on church property.

Those involved in our community sites are also putting lots of time into outreach through United Baptist Church and Peace Chapel Church. Pastors and deacons persistently continue to encourage parishioners and others in the community to pay a visit. UBC is also working to assist senior citizens with transportation and to promote the Brooklyn site to other nearby churches.

And as if the devoted, one-on-one service wasn’t enough to draw people in, all services at these sites are completely free.

Our country’s most vulnerable populations deserve the highest-quality care and protection from COVID-19. With our Brooklyn and South L.A. sites, Worksite Labs demonstrates what it means to love our neighbors of all backgrounds.

Gary Frazier is CEO of Worksite Labs.